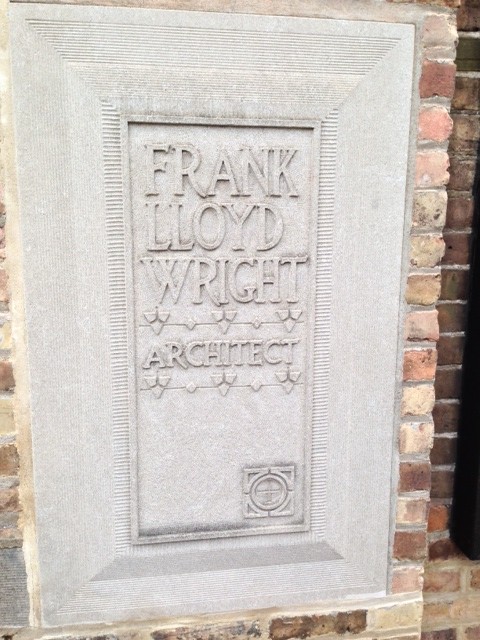

In keeping with my new-found passion (to visit as many Frank Lloyd Wright [FLW] buildings as I can), I went to Oak Park a week ago to see Frank Lloyd Wright’s first home and studio. I found the experience both anticlimactic and bracing.

As an artist preoccupied with words, languages, and story telling, I often take nourishment from other forms of art–looking for particular narratives or themes, or the emotional resonance of the work, or the intellectual energy of specific choices. In my life, I have been greatly moved by painting, poetry, theater, architecture, landscapes, dance, textiles, and pottery. I’m very receptive to beauty, movement, light and joy, and also melancholy. Thus my favorite seasons are Spring and Fall (could I call them renewal and maturity?).

I very much enjoyed my afternoon in Oak Park because it encouraged me. In museums, we typically encounter artists at the height of their powers, when they have worked out their concepts and executed their master works. Retrospectives allow some insight into the creative process over time, but the works selected remain the most polished and impressive. Seeing Mr. Wright’s early accomplishments reminded me that the person who would later author the amazing FallingWater had his own slow creative evolution: Refining ideas, tuning concepts, using an iterative approach to his work. Mr. Wright seems to have had sophisticated taste from an early age, and to have collaborated with master craftsmen who excelled in their own right. I believe that this dialogue between artists invigorated his work–it certainly invigorates mine. But I was reminded that even great geniuses have moderately sized successes in the beginning. The homes I saw were lovely and impressive, but they were first steps in a very long journey. Stamina and dedication over time are key ingredients–it’s helpful to remember these aspects for my own creative journey. Here are visitors on a tour of his studio, which is next to his first home. I enjoyed visiting the studio more than the home because it was a working space, but also a marketing space, so he had made it clever–with modular stations that could be moved around–and a bit grand, with lots of natural light, high ceilings and low hanging ceiling pieces that were anchored by an interesting pulley system.

Having been so impressed by the work of his late career, it was instructive to see work from the beginning of his career and consider the through-lines, the preoccupations and themes, that withstood time.

Some themes (according to me):

- Light versus dark–where light is allowed and where light is limited in his spaces.

- Containment versus expansion (this the tour guides emphasize as compression and release)–narrow hallways leading into large rooms or outdoor spaces.

- Privacy versus view–setting high windows in busy neighborhoods that only show trees and sky as a view.

- Geometry and order–lots of repeating themes and patterns.

- Spaces within spaces–creating little rooms within larger rooms–like the high-backed dining room chairs he preferred, creating a center of intimacy during dinner. Or delineating sub-spaces within larger rooms, so there is a reading/library corner, and a music corner within a larger living room.

- The primacy of the living spaces over the bedrooms, kitchen, or bathroom spaces.

- Finding the right furniture for the space and the theme of the space. There are story-telling murals on the walls of his Oak Park home, which influence the rest of the furniture, colors and patterns in the rooms.

- A dislike for clutter. Working after an era with more elaborate decorative patterns and fabrics–FLW’s style is relatively sparse and geometrical.

- Fitting homes into their landscapes, creating a dialogue between man and nature–Organic Architecture is the term Mr. Wright coined, with FallingWater as the preeminent rendering of this philosophy.

Mr. Wright belonged to a Unitarian Church in Oak Park, which was a relatively new suburb to Chicago in the 1890s. He built many homes for others in his congregation–there are about 30 FLW homes in the area, and there are about 20 on the walking tour near his studio.You can see the rapid evolution of his taste through his early houses. This grand home was at a time when he was experimenting with Mayan decorative themes.

This private home illustrates his interest in Japanese temple architecture.

This private home is considered the first of his prairie-style homes–which feel to me Japanese influenced, with an added concern for the privacy of the family, protecting them from onlookers. (Strangely prescient considering the number of visitors to Oak Park circling the streets scavenging for his legacy.)

Visiting FLW’s home helped me understand why his later designs have such limited and oddly placed windows. When Mr. Wright moved to Oak Park, it was mostly plains and dirt roads, with very few houses. However, over his ten years in the neighborhood, the lots started filling up with new houses, and he soon had a next door neighbor, uncomfortably close to his dining room windows. He filled in his original windows, and installed high windows in his dining room, so he would still have light and privacy. This experience must have been formative because privacy for homeowners really influenced his architectural choices going forward even for homes with many acres of land in rural areas like the Kentuck Knob house.

I can’t wait to discover more of his mid-career designs like Taliesin in Wisconsin.

One reply on “Frank Lloyd Wright: Beginnings”

And then there are those artists whose first production is their most amazing, like Orson Welles. Who would want that, though?